Learning Objective

- State Avogadro’s Law and its underlying assumptions

- Avogadro’s Law Example – When building a new internet site, it is desirable to attain and place a copyright notice on your web page so as to announce your ownership towards any perform that is displayed here from time to time.

- If I shake my can of soda, it will release more molecules into the airspace. The pressure of that can is directly proportional to the mole number of molecules in that space.

- Other examples are: Car tires in hot weather; Aerosol can; Avogadro’s Law: The Volume Amount Law. Avogadro’s law states that for constant temperature, pressure, and volume, all the gases contain an equal number of molecules. 1 mole of any gas at NTP occupies a volume of 22.4L.

This video is a brief discussion on Avogadro's Law, which describes the relationship between the volume of a gas and the amount of the gas in moles under con.

Key Points

- The number of molecules or atoms in a specific volume of ideal gas is independent of size or the gas’ molar mass.

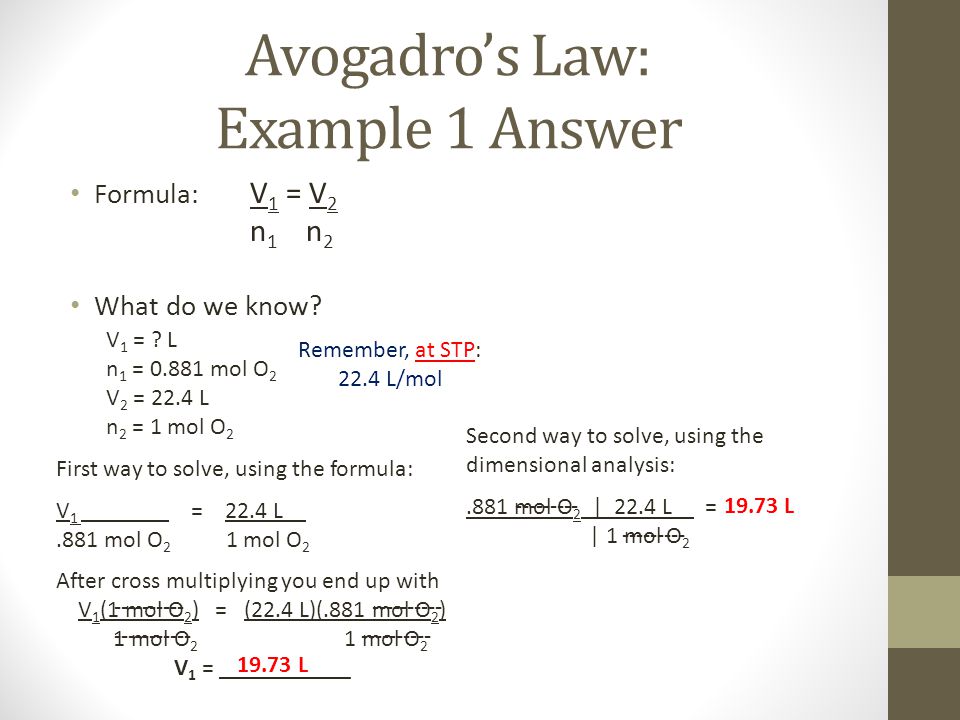

- Avogadro’s Law is stated mathematically as follows: [latex]frac{V}{n} = k[/latex] , where V is the volume of the gas, n is the number of moles of the gas, and k is a proportionality constant.

- Volume ratios must be related to the relative numbers of molecules that react; this relationship was crucial in establishing the formulas of simple molecules at a time when the distinction between atoms and molecules was not clearly understood.

Term

- Avogadro’s Lawunder the same temperature and pressure conditions, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of particles; also referred to as Avogadro’s hypothesis or Avogadro’s principle

Definition of Avogadro’s Law

Avogadro’s Law (sometimes referred to as Avogadro’s hypothesis or Avogadro’s principle) is a gas law; it states that under the same pressure and temperature conditions, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules. The law is named after Amedeo Avogadro who, in 1811, hypothesized that two given samples of an ideal gas—of the same volume and at the same temperature and pressure—contain the same number of molecules; thus, the number of molecules or atoms in a specific volume of ideal gas is independent of their size or the molar mass of the gas. For example, 1.00 L of N2 gas and 1.00 L of Cl2 gas contain the same number of molecules at Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP).

Avogadro’s Law is stated mathematically as:

[latex]frac{V}{n} = k[/latex]

V is the volume of the gas, n is the number of moles of the gas, and k is a proportionality constant.

As an example, equal volumes of molecular hydrogen and nitrogen contain the same number of molecules and observe ideal gas behavior when they are at the same temperature and pressure. In practice, real gases show small deviations from the ideal behavior and do not adhere to the law perfectly; the law is still a useful approximation for scientists, however.

Significance of Avogadro’s Law

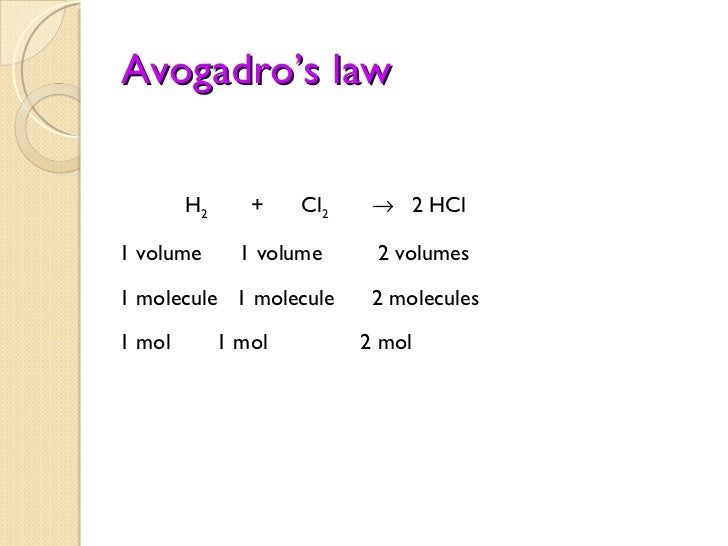

Discovering that the volume of a gas was directly proportional to the number of particles it contained was crucial in establishing the formulas for simple molecules at a time (around 1811) when the distinction between atoms and molecules was not clearly understood. In particular, the existence of diatomic molecules of elements such as H2, O2, and Cl2 was not recognized until the results of experiments involving gas volumes was interpreted.

Early chemists calculated the molecular weight of oxygen using the incorrect formula HO for water. This lead to the molecular weight of oxygen being miscalculated as 8, rather than 16. However, when chemists found that an assumed reaction of H + Cl [latex]rightarrow[/latex] HCl yielded twice the volume of HCl, they realized hydrogen and chlorine were diatomic molecules. The chemists revised their reaction equation to be H2 + Cl2[latex]rightarrow[/latex] 2HCl.

When chemists revisited their water experiment and their hypothesis that [latex]HO rightarrow H + O[/latex], they discovered that the volume of hydrogen gas consumed was twice that of oxygen. By Avogadro’s Law, this meant that hydrogen and oxygen were combining in a 2:1 ratio. This discovery led to the correct molecular formula for water (H2O) and the correct reaction [latex]2H_2O rightarrow 2H_2 + O_2[/latex].

Show SourcesBoundless vets and curates high-quality, openly licensed content from around the Internet. This particular resource used the following sources:

http://www.boundless.com/

Boundless Learning

CC BY-SA 3.0.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avogadro’s%20Law

Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 3.0.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avogadro’s_law

Wikipedia

CC BY-SA 3.0.

http://nongnu.askapache.com/fhsst/Chemistry_Grade_10-12.pdf

GNU FDL.

http://www.chem1.com/acad/webtext/gas/gas_2.html

Steve Lower’s Website

CC BY-SA.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hofmann_voltameter.svg

Wikimedia

CC BY-SA 3.0.

Avogadro's Law:

Ten Examples

| Boyle's Law | Combined Gas Law |

| Charles' Law | Ideal Gas Law |

| Gay-Lussac's Law | Dalton's Law |

| Diver's Law | Graham's Law |

| No Name Law | Return to KMT & Gas Laws Menu |

Discovered by Amedo Avogadro, of Avogadro's Hypothesis fame. The ChemTeam is not sure when, but probably sometime in the early 1800s.

Gives the relationship between volume and amount when pressure and temperature are held constant. Remember amount is measured in moles. Also, since volume is one of the variables, that means the container holding the gas is flexible in some way and can expand or contract.

If the amount of gas in a container is increased, the volume increases.

If the amount of gas in a container is decreased, the volume decreases.

Why?

Suppose the amount is increased. This means there are more gas molecules and this will increase the number of impacts on the container walls. This means the gas pressure inside the container will increase (for an instant), becoming greater than the pressure on the outside of the walls. This causes the walls to move outward. Since there is more wall space the impacts will lessen and the pressure will return to its original value.

The mathematical form of Avogadro's Law is:

| V | |

| ––– | = k |

| n |

This means that the volume-amount fraction will always generate a constant if the pressure and temperature remain constant.

Let V1 and n1 be a volume-amount pair of data at the start of an experiment. If the amount is changed to a new value called n2, then the volume will change to V2.

We know this:

| V1 | |

| ––– | = k |

| n1 |

And we know this:

| V2 | |

| ––– | = k |

| n2 |

Since k = k, we can conclude:

| V1 | V2 | |

| ––– | = | ––– |

| n1 | n2 |

This equation will be very helpful in solving Avogadro's Law problems. You will also see it rendered thusly:

V1 / n1 = V2 / n2

Sometimes, you will see Avogadro's Law in cross-multiplied form:

V1n2 = V2n1

Avogadro's Law is a direct mathematical relationship. If one gas variable (V or n) changes in value (either up or down), the other variable will also change in the same direction. The constant K will remain the same value.

Example #1: 5.00 L of a gas is known to contain 0.965 mol. If the amount of gas is increased to 1.80 mol, what new volume will result (at an unchanged temperature and pressure)?

Solution:

I'll use V1n2 = V2n1(5.00 L) (1.80 mol) = (x) (0.965 mol)

x = 9.33 L (to three sig figs)

Example #2: A cylinder with a movable piston contains 2.00 g of helium, He, at room temperature. More helium was added to the cylinder and the volume was adjusted so that the gas pressure remained the same. How many grams of helium were added to the cylinder if the volume was changed from 2.00 L to 2.70 L? (The temperature was held constant.)

Solution:

1) Convert grams of He to moles:

2.00 g / 4.00 g/mol = 0.500 mol

2) Use Avogadro's Law:

V1 / n1 = V2 / n22.00 L / 0.500 mol = 2.70 L / x

x = 0.675 mol

3) Compute grams of He added:

0.675 mol − 0.500 mol = 0.175 mol(0.175 mol) (4.00 g/mol) = 0.7 grams of He added

Example #3: A balloon contains a certain mass of neon gas. The temperature is kept constant, and the same mass of argon gas is added to the balloon. What happens?

(a) The balloon doubles in volume.

(b) The volume of the balloon expands by more than two times.

(c) The volume of the balloon expands by less than two times.

(d) The balloon stays the same size but the pressure increases.

(e) None of the above.

Solution:

We can perform a calculation using Avogadro's Law:V1 / n1 = V2 / n2

Let's assign V1 to be 1 L and V2 will be our unknown.

Let us assign 1 mole for the amount of neon gas and assign it to be n1.

The mass of argon now added is exactly equal to the neon, but argon has a higher gram-atomic weight (molar mass) than neon. Therefore less than 1 mole of Ar will be added. Let us use 1.5 mol for the total moles in the balloon (which will be n2) after the Ar is added. (I picked 1.5 because neon weighs about 20 g/mol and argon weighs about 40 g/mol.)

1 / 1 = x / 1.5

x = 1.5

answer choice (c).

Example #4: A flexible container at an initial volume of 5.120 L contains 8.500 mol of gas. More gas is then added to the container until it reaches a final volume of 18.10 L. Assuming the pressure and temperature of the gas remain constant, calculate the number of moles of gas added to the container.

Solution:

V1 / n1 = V2 / n2| 5.120 L | 18.10 L | |

| –––––––– | = | –––––– |

| 8.500 mol | x |

x = 30.05 mol <--- total moles, not the moles added

30.05 − 8.500 = 21.55 mol (to four sig figs)

Notice the specification in the problem to determine moles of gas added. The Avogadro Law calculation gives you the total moles required for that volume, NOT the moles of gas added. That's why the subtraction is there.

Example #5: If 0.00810 mol neon gas at a particular temperature and pressure occupies a volume of 214 mL, what volume would 0.00684 mol neon gas occupy under the same conditions?

Solution:

1) Notice that the same conditions are the temperature and pressure. Holding those two constant means the volume and the number of moles will vary. The gas law that describes the volume-mole relationship is Avogadro's Law:

| V1 | V2 | |

| ––– | = | –––– |

| n1 | n2 |

2) Substituting values gives:

| 214 mL | V2 | |

| ––––––––– | = | –––––––––– |

| 0.00810 mol | 0.00684 mol |

3) Cross-multiply and divide for the answer:

V2 = 181 mL (to three sig figs)When I did the actual calculation for this answer, I used 684 and 810 when entering values into the calculator.

4) You may find this answer interesting:

Dividing PV1 = n1RT by PV2 = n2 RT, we get

RT, we getV1/V2 = n1/n2

V2 = V1n2/n1

V2 = [(214 mL) (0.00684 mol)] / 0.00810 mol

V2 = 181 mL

In case you don't know, PV = nRT is called the Ideal Gas Law. You'll see it a bit later in your Gas Laws unit, if you haven't already.

Example #6: A flexible container at an initial volume of 6.13 L contains 7.51 mol of gas. More gas is then added to the container until it reaches a final volume of 13.5 L. Assuming the pressure and temperature of the gas remain constant, calculate the number of moles of gas added to the container.

Solution:

1) Let's start by rearranging the Ideal Gas Law (which you'll see a bit later or you can go review it right now):

PV = nRTV/n = RT / P

R is, of course, a constant.

2) T and P are constant, as stipulated in the problem. Therefore, we can write this:

k = RT / Pwhere k is some constant.

3) Therefore, this is true:

V/n = k

4) Given V and n at two different sets of conditions, we have:

V1 / n1 = k

V2 / n2 = k

5) Since k = k, we have this relation:

V1 / n1 = V2 / n2

6) Insert data and solve:

6.13 / 7.51 = 13.5 / n(6.13) (n) = (13.5) (7.51)

n = [(13.5) (7.51)] / 6.13

n = 16.54 mol (this is not the final answer)

7) Final step:

16.54 − 7.51 = 9.03 mol (this is the number of moles of gas that were added)

Example #7: A container with a volume of 25.47 L holds 1.050 mol of oxygen gas (O2) whose molar mass is 31.9988 g/mol. What is the volume if 7.210 g of oxygen gas is removed from the container, assuming the pressure and temperature remain constant?

Solution #1:

1) Initial mass of O2:

(1.050 mol) (31.9988 g/mol) = 33.59874 g

2) Final mass of O2:

33.59874 − 7.210 = 26.38874 g

3) Final moles of O2:

26.38874 g / 31.9988 g/mol = 0.824679 mol

4) Use Avogadro's Law:

V1 / n1 = V2 / n225.47 L / 1.050 mol = V2 / 0.824679 mol

V2 = 20.00 L

Solution #2:

1) Let's convert the mass of O2 removed to moles:

7.210 g / 31.9988 g/mol = 0.225321 mol

2) Subtract moles of O2 that got removed:

1.050 mol − 0.225321 mol = 0.824679 mol

3) Use Avogadro's Law as above.

Solution #3:

1) This solution depends on seeing that the mass ratio is the same as the mole ratio. Allow me to explain by using Avogadro's Law:

| V1 | V2 | |

| –––– | = | –––– |

| n1 | n2 |

2) Replace moles with mass divided by molar mass:

| V1 | V2 | |

| –––––––––– | = | –––––––––– |

| mass1 / MM | mass2 / MM |

3) Since the molar mass is of the same substance (oxygen in this case), they cancel out leaving us with this:

| V1 | V2 | |

| –––– | = | –––– |

| mass1 | mass2 |

4) Solve using the appropriate values

| 25.47 L | V2 | |

| –––––––– | = | –––––––– |

| 33.59874 g | 26.38874 g |

V2 = 20.00 L

Example #8: What volume (in L) will 5.5 g of oxygen gas occupy if 2.2 g of the oxygen gas occupies 3.0 L? (Under constant pressure and temperature.)

Solution:

1) State the ideal gas law:

| P1V1 | P2V2 | |

| ––––– | = | ––––– |

| n1T1 | n2T2 |

Note that it is the full version which includes the moles of gas. Usually a shortened version with the moles not present is used. Since grams are involved (which leads to moles), we choose to use the full version.

2) The problem states that P and T are constant:

| V1 | V2 | |

| ––– | = | ––– |

| n1 | n2 |

3) Cross-multiply and rearrange to isolate V2:

V2n1 = V1n2V2 = (V1) (n2 / n1)

4) moles = mass / molecular weight:

n = mass / mwV2 = (V1) [(mass2 / mw) / (mass1 / mw)]

5) mw is a constant (since they are both the molecular weight of oxygen), which means it can be canceled out:

V2 = (V1) (mass2 / mass1)

6) Solve:

V2 = (3.0 L) (5.5 g / 2.2 g)V2 = 7.5 L

Example #9: At a certain temperature and pressure, one mole of a diatomic H2 gas occupies a volume of 20 L. What would be the volume of one mole of H atoms under those same conditions?

Solution:

One mole of H2 molecules has 6.022 x 1023 H2 molecules.One mole of H atoms has 6.022 x 1023 H atoms.

The number of independent 'particles' in each sample is the same.

Therefore, the volumes occupied by the two samples are the same. The volume of the H atoms sample is 20 L.

By the way, I agree that one mole of H2 has twice as many atoms as one mole of H atoms. However, the atoms in H2 are bound up into one mole of molecules, which means that one molecule of H2 (with two atoms) counts as one independent 'particle' when considering gas behavior.

Example #10: A flexible container at an initial volume of 6.13 L contains 8.51 mol of gas. More gas is then added to the container until it reaches a final volume of 15.5 L. Assuming the pressure and temperature of the gas remain constant, calculate the number of moles of gas added to the container.

Solution:

1) State Avogadro's Law in problem-solving form:

| V1 | V2 | |

| ––– | = | –––– |

| n1 | n2 |

2) Substitute values into equation and solve:

| 6.13 L | 15.5 L | |

| ––––––– | = | –––––– |

| 8.51 mol | x |

x = 21.5 mol

3) Determine moles of gas added:

21.5 mol − 8.51 mol = 13.0 mol (when properly rounded off)

Bonus Example: A cylinder with a movable piston contains 2.00 g of helium, He, at room temperature. More helium was added to the cylinder and the volume was adjusted so that the gas pressure remained the same. How many grams of helium were added to the cylinder if the volume was changed from 2.00 L to 2.50 L? (The temperature was held constant.)

Solution:

1) The two variables are the volume and the amount of gas (temp and press are constant). The gas law that relates these two variables is Avogadro's Law:

| V1 | V2 | |

| ––– | = | –––– |

| n1 | n2 |

2) We convert the grams to moles:

2.00 g / 4.00 g/mol = 0.500 mol

3) Now, we use Avogadro's Law:

| 2.00 L | 2.50 L | |

| –––––––– | = | –––––– |

| 0.500 mol | x |

x = [(0.500 mol) (2.50 L)] / 2.00 L

Avogadro's Law Sample Problem Pdf

x = 0.625 mol <--- this is the ending amount of moles, not the moles of gas added

4) This is the total moles to create the 2.50 L. We need to convert back to grams:

(4.00 g/mol) (0.125 mol) = 0.500 g <--- this is the amount added.Avogadro's Law Sample

Notice that I subtracted 0.500 mol from 0.625 mol and used 0.125 mol in the calculation. This is because I want the amount added, not the final ending amount.

Avogadro's Law Examples Problems

| Boyle's Law | Combined Gas Law |

| Charles' Law | Ideal Gas Law |

| Gay-Lussac's Law | Dalton's Law |

| Diver's Law | Graham's Law |

| No Name Law | Return to KMT & Gas Laws Menu |